Shaolin monks achieve breaking bricks with heads or running across water, all rooted in Shaolin Kungfu.

Shaolin Kung Fu, originating from the Shaolin Monastery in Henan Province, China, established in 495 AD, is a comprehensive martial system intertwined with Chan Buddhism. It includes forms, weapons, qigong, and specialized conditioning methods known as the 72 Arts of Shaolin. These arts push the human body to its limits, cultivating Qi, physical resilience, and spiritual enlightenment.

This article summarized 12 Shaolin monks training methods from the 72 Arts; each practice illustrates the essence of Shaolin Kung Fu: harmony of body, mind, and spirit.

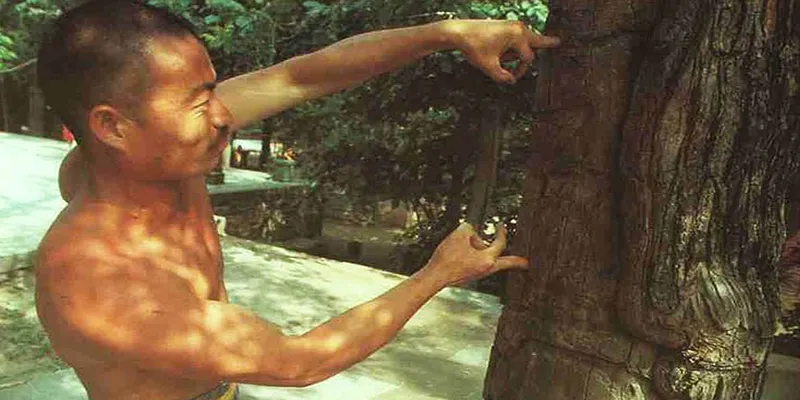

Finger Punching (Zhi Chuan)

This kung fu transforms the fingers into lethal weapons capable of piercing wood and stone.

Beginning at a young age, Shaolin monks start with gentle poking on soft surfaces like young trees or planks, gradually escalating to forceful strikes on ancient, hardened trees within the monastery grounds. This method conditions the fingers’ bones, tendons, and skin, building calluses and internal force.

Over time, it enables bursts of power in each digit, crucial for techniques like the Diamond Finger. In combat, strong fingers allow for penetrating strikes to vital points, disrupting an opponent’s Qi flow.

Shaolin monks often train for hours daily, integrating breathing exercises to channel Qi into the fingertips, preventing injury and enhancing focus. Upon mastery, the fingers are no longer just tools for grasping; they possess the structural integrity to support the entire body’s weight, serving as a one-finger handstand.

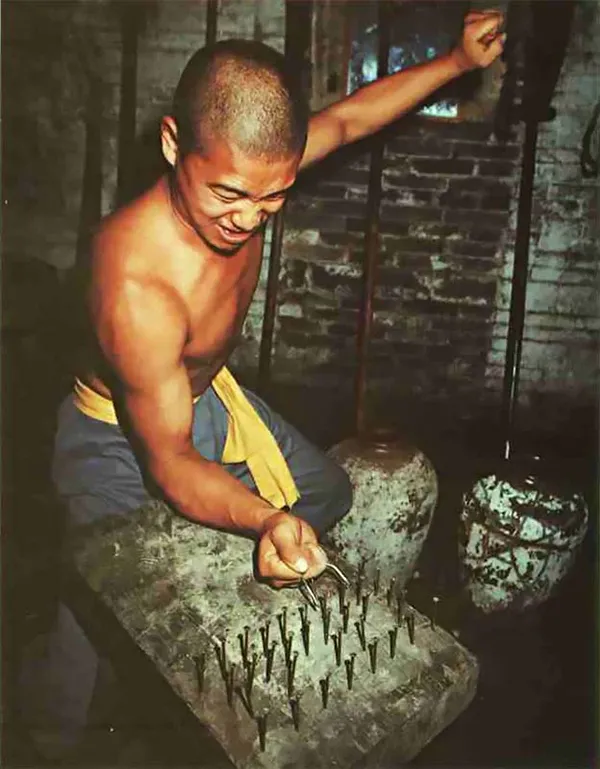

Pulling Out Nails (Bo Ding Gong)

Bo Ding Gong is the art of developing immense locking force in the thumb, index, and middle fingers to manipulate joints and seize opponents.

Grip strength in Shaolin is not measured by gym equipment but by the conquest of friction and resistance. The Shaolin monks begins this practice by driving 108 nails into a wooden plank. The initial task is to remove them using the thumb, index, and middle fingers. This mimics the “eagle claw” or locking grip used in grappling (Chin Na).

The progression is strict: once the first stage is effortless, the student must switch to using the thumb, ring, and pinky fingers—the weaker digits. As proficiency grows, nails are driven deeper and allowed to rust, increasing resistance up to 1,000 nails in advanced stages. A master of Bo Ding Gong can extract a rusted nail with two fingers, or even one.

In combat, this translates to an inescapable grip that can crush vulnerable points or seize an attacker’s weapon with terrifying force. Beyond physical benefits, it cultivates patience and precision.

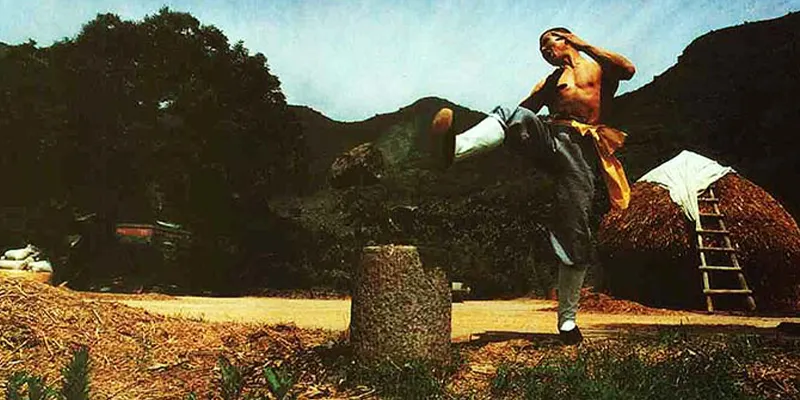

Striking with Foot (Zu She Gong)

This kung fu hardens the feet into bludgeoning instruments capable of throwing heavy opponents with a single targeted kick.

Training begins deceptively simply: the young Shaolin monk kicks small rocks with bare feet during daily strolls. It is a lesson in precision and pain tolerance. As the muscles and skin harden, the size of the stones increases.

The Shaolin monks eventually graduates to striking boulders and kicking large stones to launch them a specific distance. This method hardens the feet’s skin and bones, enhances balance, and integrates with kicking forms in Kung Fu styles like Northern Shaolin.

A master can use this hardened kick to sweep an opponent’s legs or strike the lower body with enough force to tip and throw them, ostensibly as far as they can kick the stone they trained with.

Ringing Round a Tree (Bao Shu Gong)

Also known as Maitreya, it entails wrapping arms around a tree trunk and squeezing or pulling to strengthen upper body muscles and internal force for injurious combat clasps.

Shaolin monks start with smaller trees, hugging and exerting force to train arms, chest, abdomen, and Qi flow. Naturally, the tree does not move, but the monk’s body transforms in the attempt.

This exercise is repeated several times a day, every day, for life. Results typically manifest after the first year. As the chest, stomach, and arm muscles achieve superhuman density, the student begins to shake the trunk, causing leaves to fall. The ultimate practice is the ability to uproot the tree or lift its equivalent weight.

In a martial context, this can crush an opponent’s ribs or spine, utilizing the “flows of inner force” developed against nature itself.

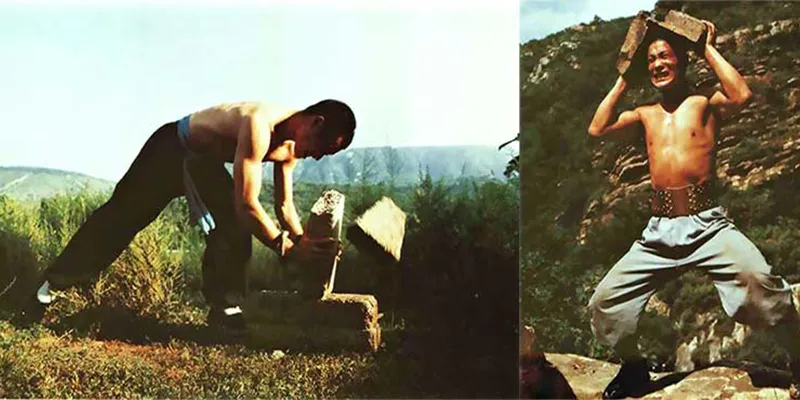

Iron Head (Tie Tou Gong)

Iron Head training reshapes the skull bones and strengthens the neck to turn the head into a battering ram that can shatter stone.

Initial training uses layers of fabric to cushion gentle hits, gradually removing protection as the head toughens. Shaolin monks progress to headstands, breaking objects atop the head, and even withstanding drills without penetration. In combat, a hardened head delivers knockdown blows or breaks weapons

The training diversifies to include sleeping in headstand positions, knocking skulls together with fellow monks, and crumpling stone slabs. Crucially, this is an internal exercise as much as an external one; without cultivating Qi to protect the brain and “round off” the external force, injury is inevitable.

A master can withstand blows from iron bars or, as in the case of Master Zhao Rui, withstand an electric drill to the temple without breaking the skin.

One Finger of Chan Meditation (Yi Zhi Chan Gong)

One Finger of Chan Meditation uses meditative focus to project force from a single finger, swinging or extinguishing distant flames, progressing to piercing objects for internal combat damage.

This is one of the most esoteric and difficult skills, exemplified by the legendary Master Xi Hei Zi. The training is meditative and solitary. Shaolin monks begins by hanging a weight and thrusting a finger toward it without touching it. Through years of meditation, the intent (Yi) becomes strong enough to make the weight swing.

The progression moves to candle flames. The master strikes from a distance of over 11 feet, attempting to make the flame sway with the pressure of their energy and motion. Eventually, paper shades and then glass shades are placed around the lamp. The goal is to extinguish the flame through the glass without breaking it.

In combat, this is the fabled “Dim Mak,” or death touch—the ability to disrupt an opponent’s vascular system or internal organs without leaving a physical mark on the skin.

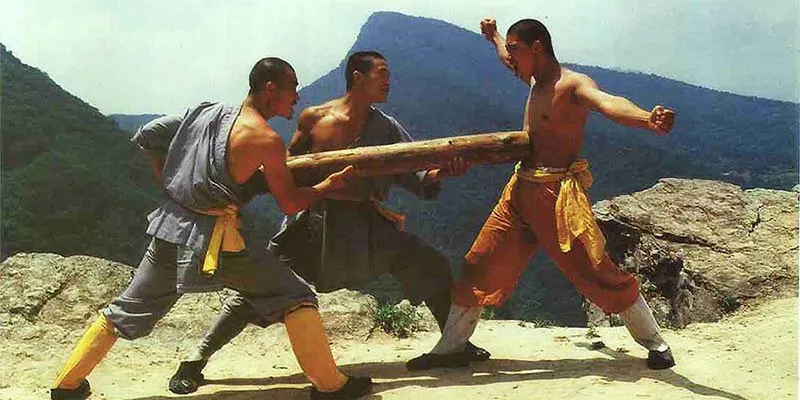

Twin Lock (Shuang Suo Gong)

Shuang Suo Gong conditions the forearms into iron bars capable of blocking heavy weapons and shattering an attacker’s limbs.

Defense is the first priority of Shaolin. The “Twin Lock” is a conditioning method where Shaolin monks lock their forearms together and strike them against each other—fist to fist, wrist to wrist.

The practice continues until the collision of forearms produces a hollow, wooden thump rather than the sound of flesh on flesh. This auditory change signals that the bones, tendons, and ligaments have calcified and thickened.

In a fight, a warrior with Twin Lock mastery does not need to dodge; they can block a blow with such solidity that the attacker’s limb is broken by the impact of the block itself.

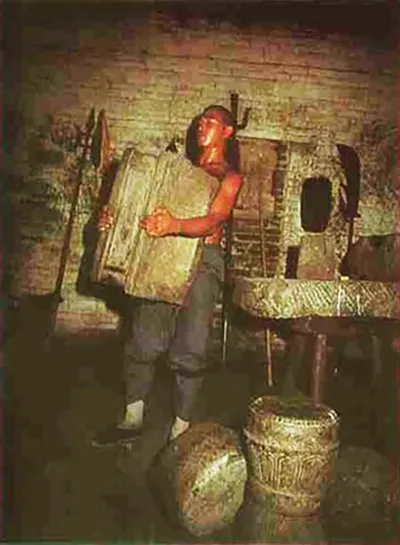

Iron Shirt (Tie Bu Shan Gong)

Iron Shirt training deadens the nerves and hardens the skin of the torso, allowing the Shaolin monks to withstand strikes from sharp and heavy objects.

To achieve the “Iron Shirt,” one must first sleep on a hard bed to condition the back. The training involves wrapping the torso in soft fabric and massaging it vigorously to stimulate blood flow and Qi.

The dynamic aspect involves a horizontal bar and a pit of sand. Shaolin monks hang from the bar and drop into the sand, impacting every part of the body. Over three years, the fabric is removed, and the body is struck—first with wooden hammers, then with iron.

The secret is mobilizing Qi to the point of impact. When the mind directs the energy to the chest or back, the flesh becomes rigid like armor. A master can repel heavy blows or sharp blades, as the energy creates a shield that physical force cannot easily penetrate.

Iron Bull (Tie Niu Gong)

Concentrating specifically on the abdominal region, Iron Bull training creates a core that is impervious to strikes, cuts, and battering rams.

While Iron Shirt covers the torso, Iron Bull focuses on the stomach—the center of Qi. Shaolin monks begin by scraping their abdomens, first with fingers and palms, then with blades. This desensitizes the skin and builds callousness.

As the skin hardens, fellow Shaolin monks deliver blows with iron hammers while the practitioner stands rooted in meditation. The pinnacle of this training is the “knocking a bell” technique, where a log battering ram weighing hundreds of pounds is swung into the monk’s stomach.

A master of Tie Niu Gong can withstand stabs and heavy artillery-level force to the gut without flinching.

Skill of Light Body (Jin Shen Shu)

This art of weightlessness allows a monk to move with such agility that they can run across water or balance on fragile surfaces.

Often depicted in movies as “wire-fu,” the Skill of Light Body is a result of arduous weight training and balance work. Ancient texts describe monks resting on branches like butterflies. The training method involves a giant clay bowl filled with water. The Shaolin monk walks on the rim of the bowl carrying a heavy backpack filled with iron.

Every month, water is removed from the bowl, making it lighter and more unstable and more iron is added to the backpack. The Shaolin monks must walk without tipping the bowl. Eventually, the bowl is empty, and the backpack is full. When the weights are removed, the monk feels light as air.

Advanced Shaolin monks practice running across grass without bending the blades or, as demonstrated recently, running across the surface of a lake on floating plywood mats.

Monk Pillar Skill

The Pillar Skill develops absolute balance and leg strength by forcing the monk to hold squatting positions on precarious perches.

Shaolin Monks train by standing on two vertical pillars, initially performing squats. To raise the stakes, a sharp bamboo stick is placed beneath them.

They hold bowls of water in each hand and one on the head to enforce perfect posture and stillness. As the Shaolin monk masters the water, it is replaced with oil lamps. If the oil spills, it burns, leading immediate pain.

A Shaolin monk master can remain in this precarious squat, completely motionless and balanced, for two hours or more. This builds a lower body structure that cannot be uprooted in combat.

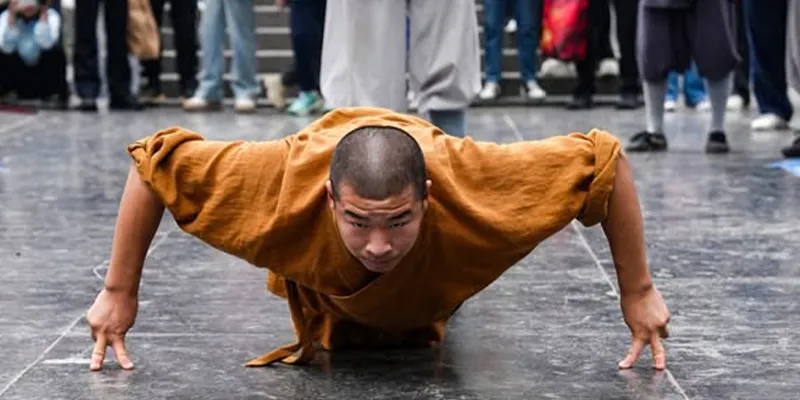

Diamond Finger (Ya Zhi Jin Gang Fa)

The ultimate expression of finger strength, this hard Qigong skill allows a monk to support their entire body weight on a single index finger.

While similar to the basic “Finger Punching,” the Diamond Finger (or Buddha’s Finger) is the specific application of that strength into a static hold of immense power. It incorporates elements of the nail-pulling training and stone striking to achieve a finger capable of piercing an opponent’s chest cavity.

The most famous demonstration of this art was by the late Shaolin monk Hai Deng. Famous for his one-finger handstand, he trained by meditating with his full body weight inverted atop his index finger. Even at 90 years of age, he could perform this kung fu.

While many Shaolin monks can achieve a two-finger handstand, the one-finger variant is a rarity that signifies the highest level of “hard qigong” mastery. It is the physical manifestation of the mind conquering the body’s limitations.

Conclusion

The martial arts of the Shaolin monks are not magic. They are the result of physics, biology and willpower. From the “Iron Head” that reshapes the skull to the “Light Body” that defies gravity, these 12 Shaolin Kung Fu represent the outer limits of human potential.

Shaolin monks remind us that with enough time, pain, and dedication, the impossible becomes merely a matter of practice.