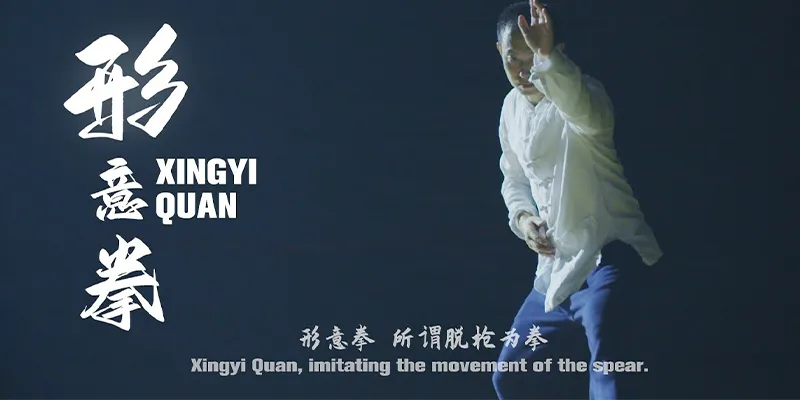

Xingyiquan, often romanized as Hsing-I Chuan, is one of China’s profound internal martial arts, emphasizing the harmony of mind, body, and intent. As a practitioner and scholar of Xingyiquan for over three decades, I approach this ancient art with deep respect and humility.

In this post, I will introduce its rich history and core techniques. Let us begin with its origins.

Xingyiquan History and Development

Ji Longfeng, also known as Ji Jike (1602–1683 CE), is widely recognized as the founder of modern Xingyiquan.

Born in Shanxi Province, Ji was a skilled spearman who, during his travels, encountered Daoist monks in the Zhongnan Mountains. There, he refined his art by integrating the “mind-intent” (yi) with physical form (xing), hence the name Xingyi—”form and intent” boxing. Ji’s system drew from the Five Elements theory of Chinese philosophy (metal, wood, water, fire, earth), which symbolizes cyclical transformations, and the movements of twelve animals.

Ji Jike transmitted his knowledge to Cao Jiwu, who further spread it through military channels. By the 18th century, Xingyiquan had branched into regional styles, primarily in Shanxi, Hebei, and Henan provinces.

Key figures include Dai Longbang (1713–1802 CE) of the Shanxi branch, who emphasized internal power and authored treatises on the art; Li Luoneng (1808–1890 CE), founder of the Hebei style, who integrated more explosive techniques; and Guo Yunshen (1829–1898 CE), Li’s student, renowned for his “half-step crushing fist” that could fell opponents with minimal movement.

During the Qing Dynasty, Xingyiquan gained prominence among bodyguards and militia, its linear, direct strikes proving effective in real combat.

The Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901 CE) saw practitioners like Che Yizhai employing it against foreign forces, blending it with nationalist fervor.

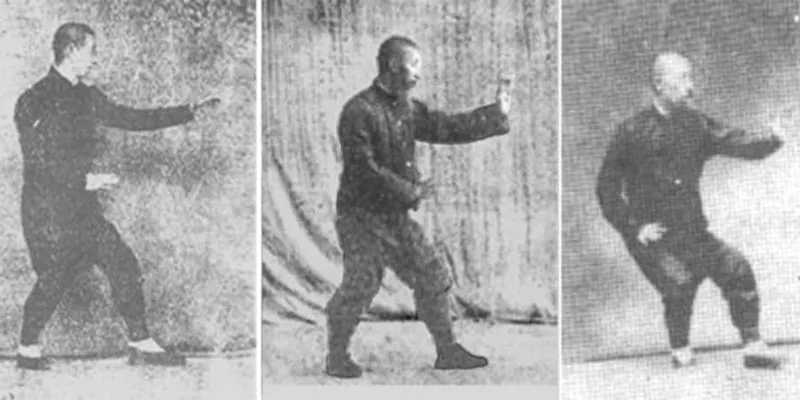

In the Republican era (1912–1949), masters such as Sun Lutang (1860–1933 CE) cross-trained in Xingyi, Taiji, and Bagua, creating the Sun style that influenced modern internal arts. Sun’s book, Xueyi Quan, remains a seminal text, detailing the integration of the three styles.

Under the People’s Republic of China (post-1949), martial arts were standardized for health and sport, sometimes diluting combative elements. Yet, dedicated lineages preserved the traditional essence.

Today, Xingyiquan is practiced globally, with organizations like the International Xingyiquan Association promoting seminars and competitions.

Core Principles of Xingyiquan

At its heart, Xingyiquan operates on the unity of san he (three harmonies): body and mind, mind and intent, intent and qi.

Xingyi focuses on nei jin, generated through relaxed structure and explosive release. The foundational stance, San Ti Shi (Three Body Posture), exemplifies this: feet shoulder-width, weight on the rear leg, arms extended as if holding a spear, with the mind focused on infinite extension.

Training progresses from static postures to dynamic movements, emphasizing zhan zhuang to refine qi flow. Practitioners hold this for extended periods to build root, alignment, and yi.

Xingyiquan Techniques: Five Elements

Xingyiquan’s techniques lie in the five elements fists, each corresponding to a natural element and organ in traditional Chinese medicine.

1. Pi Quan (Splitting Fist) – Metal Element: Mimicking an axe cleaving wood, this downward strike splits the opponent’s guard. The movement starts from San Ti Shi, advancing with a stomping step while the lead hand chops vertically. It targets the centerline, emphasizing whole-body power from the dantian. In application, it counters grabs or high attacks, associating with the lungs for breath control.

2. Zuan Quan (Drilling Fist) – Water Element: Like a drill boring through earth, this upward spiraling punch penetrates defenses. The fist rotates inward as the body coils and uncoils, driving forward with twisting torque. It links to the kidneys, promoting fluid, adaptive movement. Practically, it’s used for underhooks or disrupting balance.

3. Beng Quan (Crushing Fist) – Wood Element: Resembling an arrow shot from a bow, this straight punch crushes forward with explosive speed. From the rear hand, it propels the body like a spear thrust, covering distance rapidly. Associated with the liver, it fosters growth and expansion. Beng Quan is Xingyi’s signature—direct, unyielding, and ideal for closing gaps.

4. Pao Quan (Pounding Fist) – Fire Element: Evoking a cannon’s blast, this arcing punch pounds downward or outward with concussive force. The arm whips like a fireball, generating power from hip rotation. It connects to the heart, symbolizing explosive energy. In combat, it overwhelms with overhead strikes or deflections.

5. Heng Quan (Crossing Fist)—Earth Element: Like mountains crossing paths, this horizontal strike stabilizes and redirects. The fist crosses the body, using centrifugal force to sweep or block. Tied to the spleen, it represents centering and absorption. Heng is versatile for mid-range control.

Xingyiquan Techniques: The Twelve Animal Forms

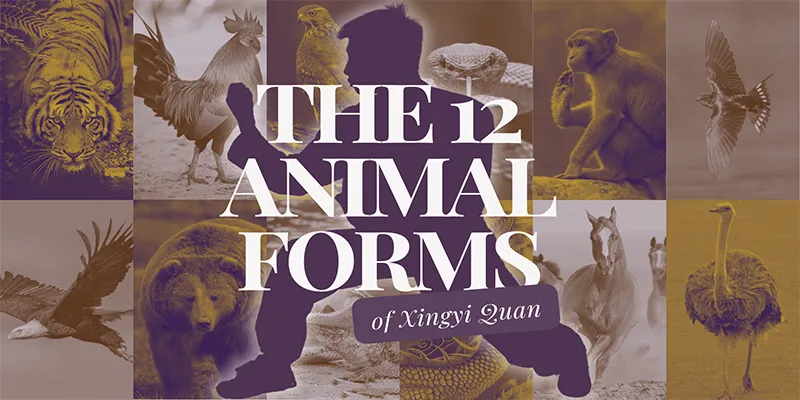

Beyond the elements, Xingyiquan incorporates Shi Er Xing (Twelve Animals), drawing inspiration from wildlife to expand its technique. Each animal embodies unique attributes, refining the five elements into specialized techniques.

- Dragon (Long Xing): Coiling and rising like a dragon ascending, for evasive, twisting strikes.

- Tiger (Hu Xing): Pouncing with ferocity, clawing downward to seize and tear.

- Monkey (Hou Xing): Agile and deceptive, with quick hops and probing attacks.

- Horse (Ma Xing): Galloping charges, stomping to unbalance foes.

- Alligator (Tuo Xing): Low, dragging movements for sweeps and takedowns.

- Cock (Ji Xing): Pecking and flapping, rapid short-range bursts.

- Swallow (Yan Xing): Skimming low then soaring, for dodging and countering.

- Sparrowhawk (Yao Xing): Circling dives, aerial strikes from above.

- Snake (She Xing): Slithering evasion, coiling to constrict.

- Tai Bird (Tai Xing): Mythical bird’s grace, balancing on one leg for kicks.

- Eagle (Ying Xing): Clutching talons, grabbing and ripping.

- Bear (Xiong Xing): Heavy, swaying power for close grappling.

These forms are practiced in sequences, often combined with the elements (e.g., Tiger with Beng for crushing pounces). Advanced Xingyiquan training includes weapons like the straight sword or spear, where empty-hand principles translate directly.

Xingyiquan Training Process

Xingyiquan beginners start with San Ti Shi, the Three Body Posture, standing with feet shoulder-width apart, weight primarily on the rear leg, one hand extended forward at nose level and the other at the hip, while aligning the body vertically and focusing the mind on infinite extension to cultivate root and qi flow.

This is complemented by basic stepping drills, where one advances or retreats in straight lines with coordinated arm movements, emphasizing relaxation and whole-body unity.

Then, students practice the Wu Xing fists, such as Pi Quan, executed by advancing from San Ti Shi with a downward chopping motion powered by hip rotation and exhalation; Zuan Quan, involving a spiraling upward punch with twisting torque from the waist; and linking them in chains to understand cyclical transformations.

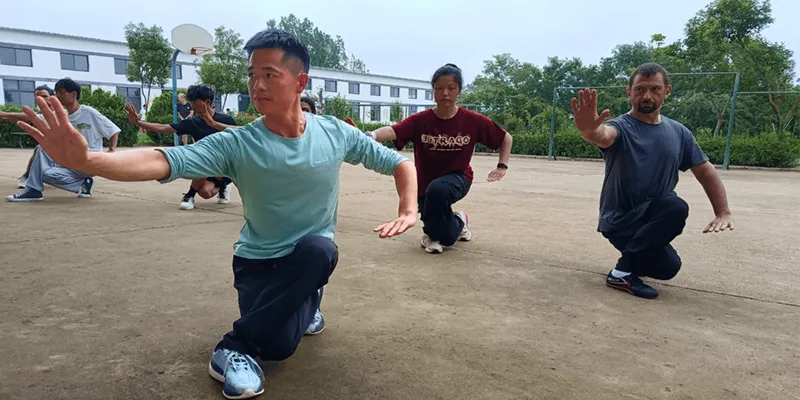

Finally, the advanced xingyiquan training incorporates the Twelve Animal Forms, like the Tiger Form with pouncing downward strikes using claw-like hands to seize and pull, or the Dragon Form with coiling twists for evasive counters, practiced in two-person sets such as sticky hands to sense and redirect opponents’ energy.

Building upon intermediate fluidity, this phase includes free sparring and neigong meditation, where Yi leads every action, achieving efficiency in real scenarios.

Xingyiquan Applications

In self-defense, Xingyiquan excels in linear confrontations, using short, powerful bursts to end threats quickly. It’s not acrobatic like Shaolin but efficient, suiting all ages. Health benefits include improved posture, circulation, and mental focus. Many practice for longevity, aligning with Daoist neigong.

Modern adaptations blend Xingyi with MMA or qigong, but traditionalists like myself emphasize purity.

FAQs

What is the relationship between Xingyiquan and Sun style Taijiquan?

Sun Lutang (founder of Sun-style Tai Chi) integrated the internal energy principles and explosive power of Xingyi Quan into the Sun-style Tai Chi system.

Sun Lutang studied Xingyi Quan under masters such as Guo Yunshen and later studied Wu style Tai Chi and Baguazhang. In the early 20th century, he combined the two to create Sun style Tai Chi Quan. Sun Tai Chi emphasizes compact movements, agile footwork, and the unity of intention and form.

It directly borrows the Five Elements and animal forms from Xingyi Quan, enhancing the soft power of Tai Chi with internal strength and direct efficiency, making it a bridge connecting the three major internal martial arts styles.

Xingyiquan pronunciation

Xingyiquan, in Mandarin Chinese, is pronounced approximately as “sheeng-ee-chwen.” In pinyin romanization, it is written as Xíngyìquán, with the tones being rising on “xíng,” falling on “yì,” and rising on “quán.”

For a more precise phonetic guide, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) renders it as [ɕǐŋ.î.tɕʰɥɛ̌n], emphasizing the aspirated “q” sound similar to “ch” in “chin.” In English approximations, it is sometimes voiced as “hsing-ee-chwan” or “shing-yi-chuan.”

Benefits of xingyiquan

Xingyiquan enhances physical health through improved posture, circulation, and joint mobility while cultivating explosive yet efficient power for self-defense in your life.